On Thursday, March 12, 2020, I was interviewed by a reporter at a newspaper in a mid-sized California city*. The topic was described to me as “a story about the panic associated with the virus — people clearing out stores of toilet paper, bottled water, etc.” I am not a topic expert on COVID-19, but was being interviewed by virtue of my expertise on collective social behavior (I did spend three years as a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins Med School in the department of Emergency Medicine, where I managed to pick up at least some epidemiology, and I regularly teach modeling contagion).

I was sent a number of questions in advance to prepare, though our conversation was over the phone. When it became apparent that I didn’t think people were overreacting, the reporter indicated that the story would probably be killed rather than reshaped to reflect more accurate information. I urged this person to flip the story and encourage people to adequately respond, but the more we talked, the less likely that seemed. Since the newspaper won’t cover it, I’m posting my brief answers to their questions here. I realize that a lot of people who follow my research will not need this information, but if anyone benefits from it, it seems worth it.

What is driving this behavior?

I think people are responding to a potential threat. There is a lot of uncertainty about what is going on. They are getting some conflicting information, but one common theme is: this is bad, and it is going to get worse before it gets better. From the epidemiological work I’ve managed to survey on COVID-19, I’d say this is accurate. My primary concern is not overreaction on the part of a few stockpilers, it’s underreaction on the part of both individuals and institutions who are not taking this serious. This is shaping up to be the worst pandemic since the 1918 Spanish flu, and could potentially be much worse in terms of both lives lost as well as economic impact. The US needs more measures to ensure social distancing, more and free access to testing and treatment, and better information put out to the public.

Is the panic worse than the threat?

Not by a long shot. This is very serious. We are maybe a couple of weeks behind Italy, and we are showing similar patterns as them and other countries when you control for when the first outbreaks were reported. In fact, the US likely has a lot more infected individuals than the numbers suggest, because of the lack of sufficient testing. In the next few weeks this is likely to get very bad, very quickly. As of today, Italy has over 17,000 confirmed cases with more than 1,200 deaths.

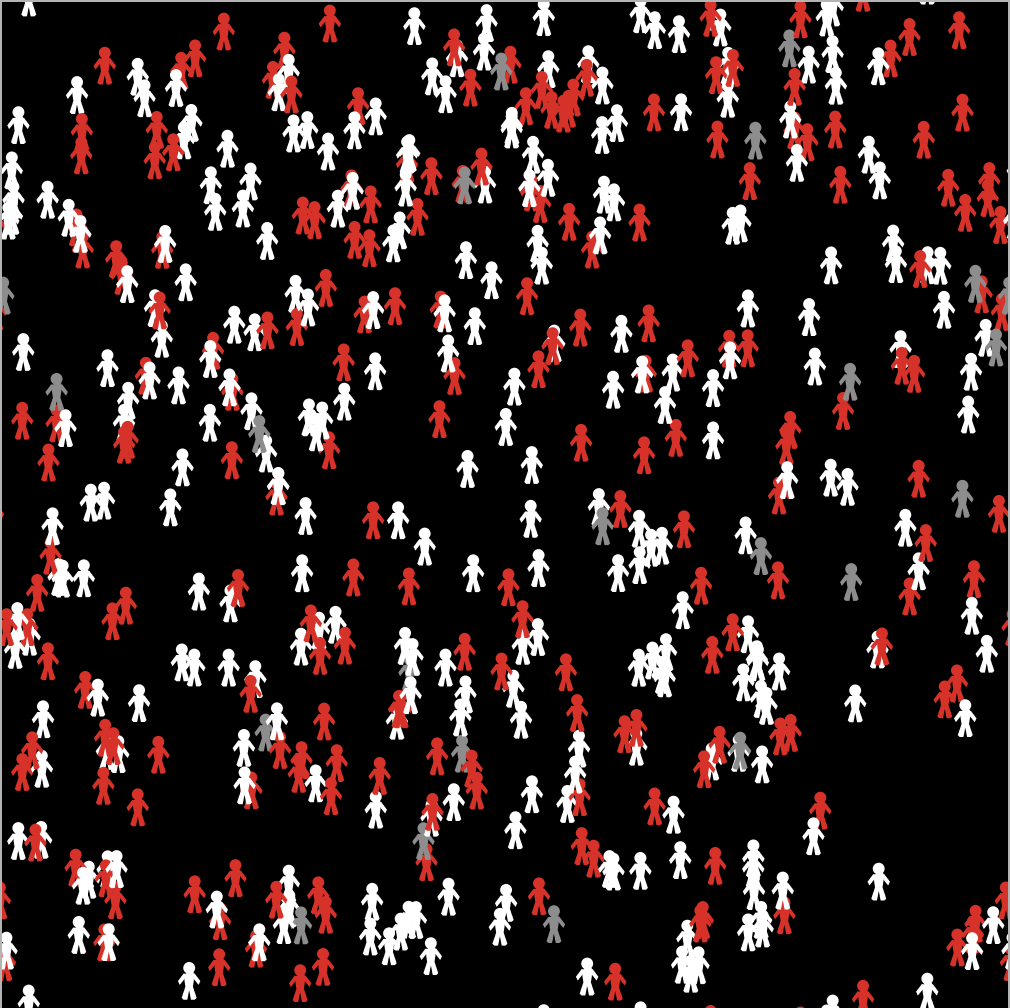

Keep in mind that we are talking about exponential increase. Some of the data from other countries suggest that, at least in the first few weeks, you can approximate the spread as a daily increase of 33%. If you start with just three cases and the number of infected increases by a third every day, in 5 days you have 12 cases. No big deal. In 10 days, you have 52 cases. In 3 weeks, you have over 1,000 cases, and in a month you’ve got 20,000 cases. Two more weeks after that, and you’ve exceeded a million cases. Now obviously there are limits to how high this number can go because of the way populations interact, but the early numbers at least are in line with how the virus has increased in countries that saw earlier outbreaks than us. We had a big lead to prepare for this, and we’ve wasted it.

Why do some people engage in this other behavior while others don’t?

I don’t know. Some people are probably more reactionary, and others are more stubborn. No one likes to have to change or cancel their plans, or be otherwise inconvenienced. Social networks and identities interact with practical and economic concerns.

How does the response to the virus compare to previous public threats (AIDS, 9-11, etc)?

We probably haven’t had a real public threat like this in 100 years. 9/11 was a vicious attack on one place at one time by a group of people who were able to exploit a weakness in a system. Look, I’m a native New Yorker and I lived in NYC in the aftermath of 9/11. The reaction from most people was a mix of solidarity – we’re in this together – and, you know, racism. Most importantly, the threat of it happening again was very small. People seem to dramatically overestimate the threat of terrorism. Even before this pandemic, most people are much more likely to die of disease than of terrorism.

AIDS is caused by a virus, so it’s perhaps more similar to now. During the AIDS crisis, the response was also completely inadequate, both by the public and by the government, and this was largely because it initially was mostly restricted to marginalized populations like gay men. But HIV is relatively difficult to transmit – you can’t catch AIDS from someone if they cough or sneeze on you or something you touch. You can catch Coronavirus that way.

Something else to remember is that the incubation period for something like flu is usually a couple of days. There’s not that much time between when you catch it and when you feel sick. With COVID-19, the time between when you catch it – and can infect others – and start showing symptoms appears to be up to two weeks! I’ve heard people say things like “There are no cases in my town yet” or “there aren’t many cases here.” Two things about this. First, there could be many people infected who aren’t yet symptomatic, who can still infect others. Second, the extent to which the US has failed to adequately test people for COVID-19 cannot be overstated. We need to be testing much, much more. I am confident that if we had an accurate picture of how the infection is spreading here, we’d have justification to be more worried.

Any advice on how not to find the balance between panic and not doing anything?

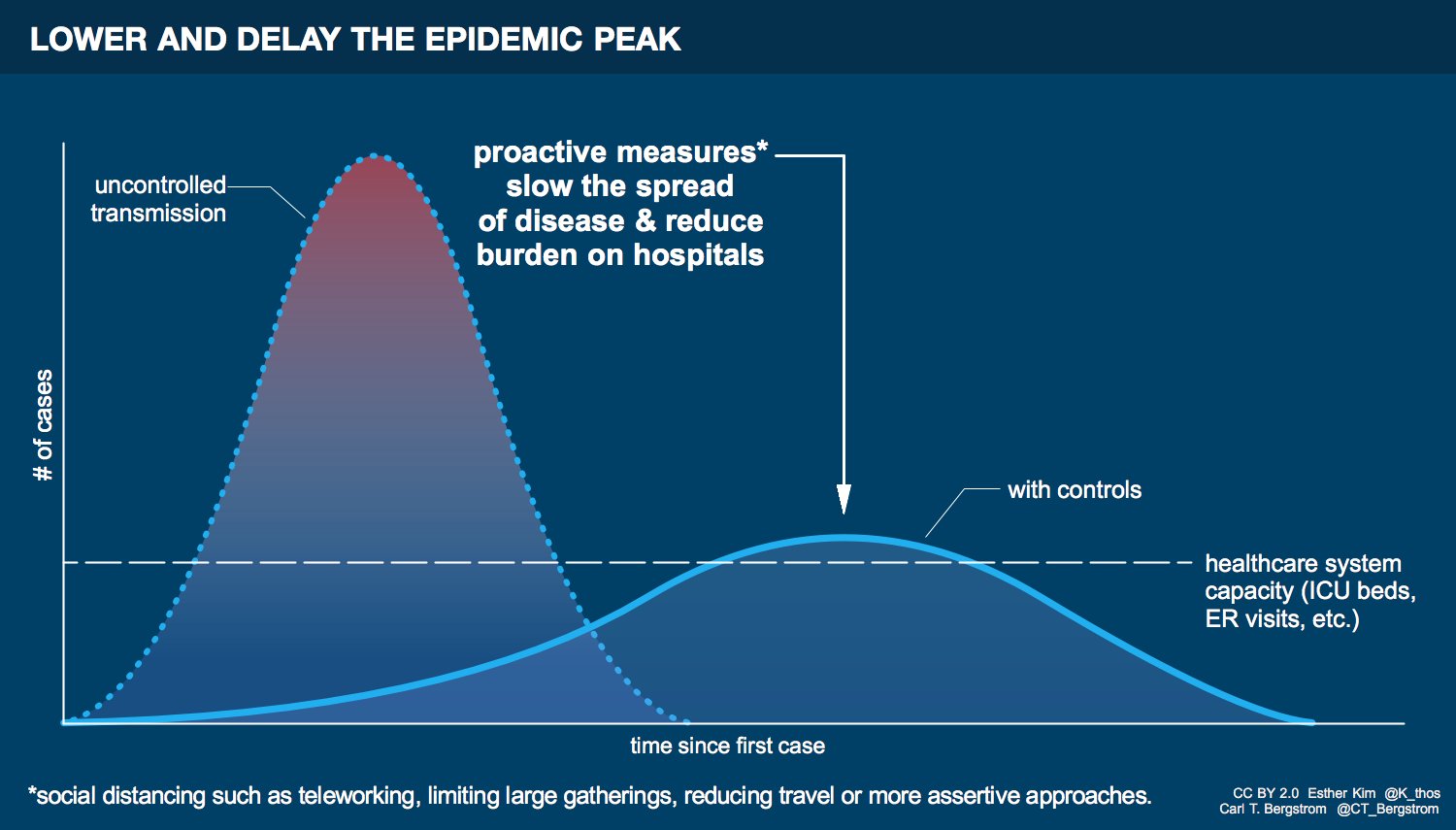

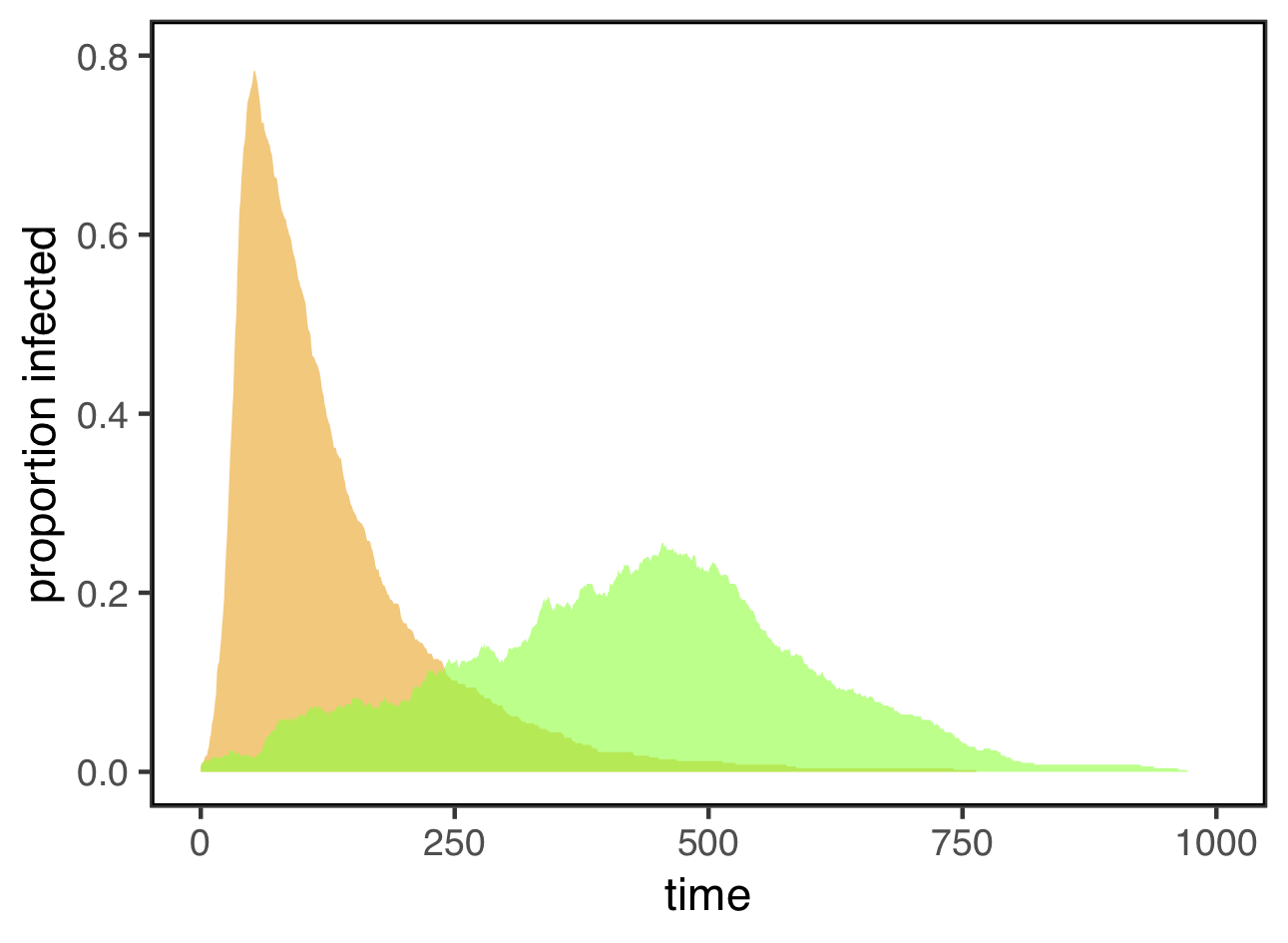

Don’t panic, but do worry. The best thing you as an individual can do is to avoid crowds, public transportation and airports, and wash your hands well and often. The Coronavirus binds to soap, so soap works better than hand sanitizer. The best thing that society can do is to encourage social distancing. This doesn’t just limit the number of infections. It can dramatically reduce the speed of infection, so that fewer people are sick at any given time. This is really important if we want to avoid overloading our hospitals, our healthcare systems, and to provide more time for new tests and treatments to be developed. It’s completely insane that any large gatherings are happening at all right now.

As for stockpiling – other countries have effectively shut down commerce as the virus has reached peak infection rates. I think it is entirely rational to cache a few weeks worth of food and other supplies. The CDC recommends a month’s worth of supplies.

Stay informed. Social media like Twitter is especially good for this. Follow experts, not pundits or politicians (but hold the politicians accountable).

*The name of the paper isn’t important. No one is perfect, and I don’t this is worth calling someone out on.